The invisible enemy should not exist is an ongoing project centering on threatened, destroyed, and missing cultural heritage. Michael Rakowitz began this work in 2007, reappearing artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq in the aftermath of the US-led invasion in 2003. Drawing from a database of reference images and information, the sculptures are constructed using papier-mâché made of Arabic-English newspapers and West Asian food packaging found in diasporic grocery stores in Chicago. The invisible enemy should not exist is a translation of “Aj ibur shapu,” the name of the Processional Way that ran through Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate in Babylon.

Included in this exhibition is a series of cylinder seals. Existing on an intimate scale, cylinder seals were small stone objects that were rolled out onto wet clay to create an impression. They are linked to the invention of cuneiform writing on clay and were used as signatures, worn around the neck as jewelry, and served as amulets. Before the Iraq Museum’s looting, the collection of seals was over 15,000.

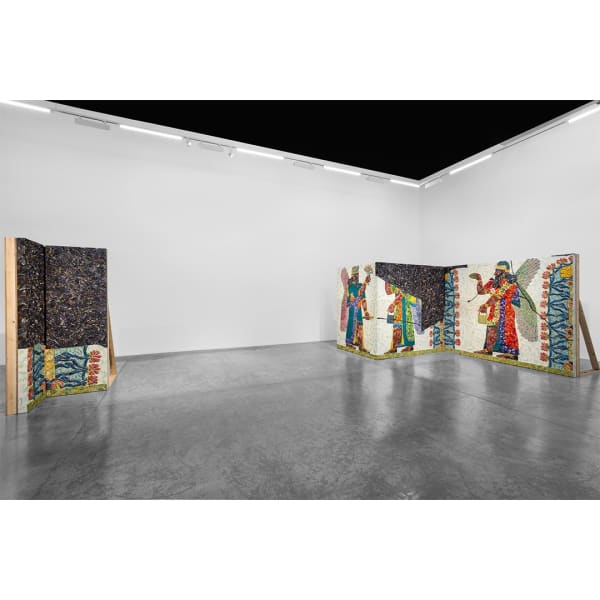

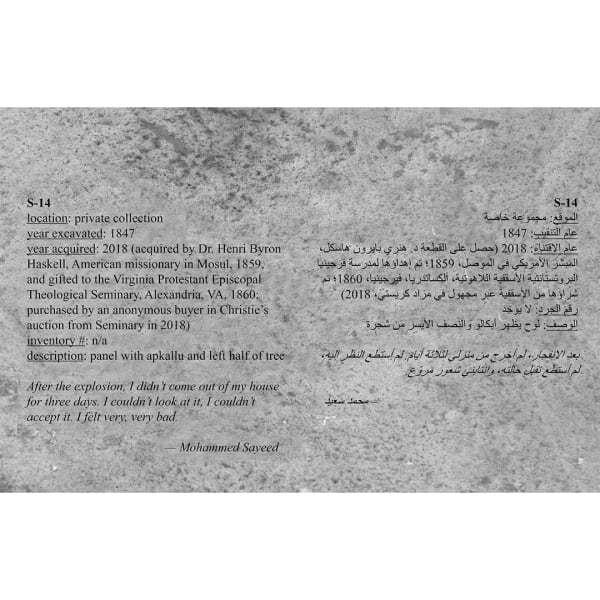

In 2018, Rakowitz began a new branch of the project. Since the mid-1800s, Western institutions like the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have participated in the systematic extraction of works from the Assyrian Northwest Palace of Kalhu, (Nimrud), near present day Mosul, Iraq. The sculptural relief panels that remained after these waves of excavations were destroyed by ISIS in 2015. Using the same logic of the first iteration of The invisible enemy should not exist, Rakowitz and his studio have been reappearing the 200 remaining panels of the palace that were in situ until their destruction in 2015. Each room of The invisible enemy should not exist (Northwest Palace of Kalhu) is installed true to its original architectural footprint. As an integral part of each room’s installation, empty spaces with museum labels indicate where the panels that still exist are held, mostly in private collections or museums in the West. These empty spaces of imperialist extraction, alongside the reappeared panels that remained in the palace until their destruction in 2015, provide a view of what the palace would have looked like the day before its destruction by ISIS, and make present the human lives that perished alongside the destroyed archaeological sites. It is a project that acknowledges the continued history of displacement in Iraq, creating a palimpsest of different moments of removal.